Why Right Wing Hates the Romila Thapars and Irfan Habibs

Today, the Right-wing ecosystem of political Hindutva is trying to revive and reinstate the state-centric, nation-centric History-writing that the Congress had done in the last century. The difference is that BJP wants to imagine an eternal Indian nation tied together with the thread of Hindutva – mainly by projecting into the past modern upper caste cultural practices.

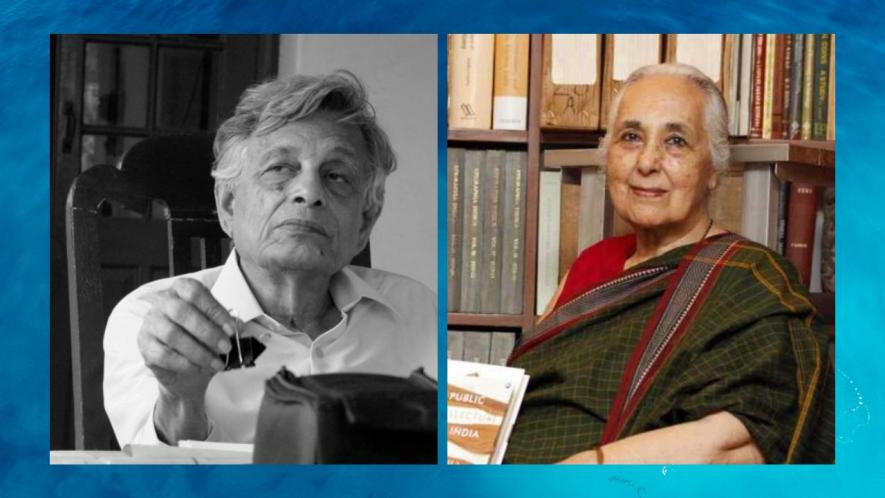

For the past few days, a short video clip has been doing the rounds on social media. It’s a short exchange between a popular Youtuber named Ranveer Allahabadia and a rightwing commentator J Sai Deepak. Allahabadia is seen asking Sai Deepak to name three people who he thinks should “leave India and never return.” Sai Deepak named the celebrated journalist Barkha Dutt and two world-renowned historians – Irfan Habib and Romila Thapar. According to Sai Deepak, they all “had harmed Indian interests in their own ways, and Bhartiya interests, and done grave injustice to facts, truth, history, and integrity.”

Sai Deepak is not alone in his deep dislike for these two historians. They are widely hated by supporters of political Hindutva and are often subjects of WhatsApp forwards that emanate from the Right-wing ecosystem. Romila Thapar is an understandable target. She was a vocal opponent of the Ram Mandir movement, and has been in the crosshairs of anyone and everyone associated with the Sangh Parivar. The hatred for Irfan Habib is driven by his critique of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its mentor, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

Yet, neither Thapar, nor Habib, have much reach. Their political statements or activism is of little consequence to the Right. They are representatives of a bigger, more long-term, battle – the battle over History, with a capital H. India’s history (with a lowercase ‘h’) has already happened; it is in the past. Its writing, which I am calling ‘History,’ exists entirely in the present.

This History is an inseparable part of nationalist identity-formation, because nationalism by its very nature must appeal to a wider, non-local, community. Other pre-modern communitarian identities get reproduced through narratives of kinship and locality. Nationalism transcends these to appeal to a wider geographical entity that is bounded by the nation-state. In the mythology of the modern capitalist society, nationalism is a common thread that ties together the supposedly independent, individual citizens with others like them. This is why ‘national’ histories must always speak of a common past of the entire people.

Till the Congress ‘system’ was the dominant political configuration in India, the Congress view of history was predominant. That is what was taught in schools and colleges and was reproduced in popular culture through cinema, arts, literature and even the preservation of monuments and their promotion through tourism.

In this ‘Congress’ view of history, India was always a nation in the making, but the people were divided by caste, and regionalism. The various ‘empires’ – Mauryas, Guptas, Mughals – attempted to realise the potential of the Indian people to crystallise into a nation, but failed repeatedly. It was only in the colonial period, that the people decided to forget their caste, creed, religion, to unite under the banner of the Indian National Congress to fight for independence. 1947, thus was the moment when “the soul of a nation, long suppressed, (found) utterance.”

Right from the beginning this ‘nationalist’/Congress view of history was opposed by Left-oriented historians. Among the first was DD Kosambi, who made early attempts to understand India’s past through the lens of Marxist class analysis and in terms of modes of production. There were others who made similar attempts with less success. The main objective was to shift the study of history to the study of its working people, to write a real people’s History and to analyse modes of production, instead of kings and empires.

R S Sharma would take this further in his study of the economic systems in the ancient period. Irfan Habib applied the same methods to his celebrated early work on the agrarian system of the Mughal empire, and Romila Thapar approached Ashoka’s reign from a Marxist-influenced perspective. This was a move to shift the terrain of research, and much of their research entered the organised university system, and began to influence future historians and history teachers. Indian historians also came to be well respected in the global academic system.

Some ‘nationalist’ historians who were sympathetic to the Congress were also influenced by the rising global prestige of Marxist historiography in the 60s and 70s. The ‘Congress’ view shifted subtly to incorporate rudimentary class and structural analysis, while claiming a radical role for the Nehruvian Congress and the Nehruvian state. The most prominent amongst the ‘nationalist-Marxist’ historians was Bipan Chandra, who influenced many younger scholars. This school had a significant role in writing school textbooks, which, in turn, informed the ideas about History in popular discourse.

A second shift took place in the late 70s and early 80s, with the rise of the Subaltern Studies group – a team of political scientists, historians, and anthropologists, with divergent theoretical positions, but united by the belief that all Indian History was ‘elitist’. They sought to recover the history of the ‘subaltern,’ the exploited and the oppressed.

By the early 90s, most of the practitioners of this group had moved to focus on the Congress, but not to write a nationalist History of the freedom struggle, but to reveal how the national movement was a struggle for establishing the hegemony of the elites, through a passive revolution. The post-colonial Nehruvian state was its result – enabling the elites to rule in the name of the people.

There was significant push-back to this critique of nationalism and the modern Indian state, from academic institutions. But not much was required. What the Subaltern Studies group was talking about was deeply counter-intuitive, and even heretical. It was difficult for lay readers to understand, for it needed a degree of training in post-structuralist theory. This is why their critique remained trapped within the universities and seminar-circuits. Their ideas never made it to school textbooks. However, formal historical scholarship, in the post-90s period has been heavily – some would say, disproportionately – influenced by the post-structuralist and post-modern turn in academics.

Today, the Right-wing ecosystem of political Hindutva is trying to revive and reinstate the state-centric, nation-centric History-writing that the Congress had done in the last century. The difference is that BJP wants to imagine an eternal Indian nation tied together with the thread of Hindutva – mainly by projecting into the past modern upper caste cultural practices. The Muslims of India have no place in this vision of the Indian ‘nation,’ and neither can this view admit class and caste oppression. So, it must attack those who speak of the historical divisions of caste and class among the peoples of the sub-continent, just as they must attack those who talk about common cultural ties between Hindus and Muslims. This is the key reason why the Right-wing hates the Romila Thapars and Irfan Habibs of our country.

The writer was a senior managing editor of ‘NDTV India’ & ‘NDTV Profit’. He runs the YouTube channel ‘Desi Democracy’ and anchors a bi-weekly show on Newsclick . The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.