The Myth of Caste-Free Metropolises

Image Coutesy: Hindustan Times

A common belief among the urban middle classes in India is that the significance of caste is greatly diminished in the urban space. It is often argued that “socio-economic” status and class are the major divisions along which stratification occurs in urban India. A common perception is that various manifestations of caste only continue in the villages, and that the processes of urbanisation and economic growth are blurring the lines of caste divisions.

An oft-repeated argument is that the extent and occurrence of atrocities against Dalits in urban India are much less as compared to in villages, though this is also disputed. Ashwini Deshpande, in an article for The Wire, showed how there still are a huge number of cases registered under the Prevention of Atrocities Act, and how that is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to crimes committed against Dalits and Adivasis as several cases go unreported. A few examples of crimes that fall under this Act are: forcing victims to eat or drink obnoxious substances, dump excreta, sewage, carcasses into their homes or compounds, land grabbing, humiliation, and sexual abuse. This shows the intensity of such crimes.

Another common myth among the urban Indians is the idea that segregation in cities, particularly in metropolitan cities, does not occur along the lines of caste. It is often argued that segregation occurs only on the basis of socio-economic status. A new working paper published by the Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, disputes this idea.

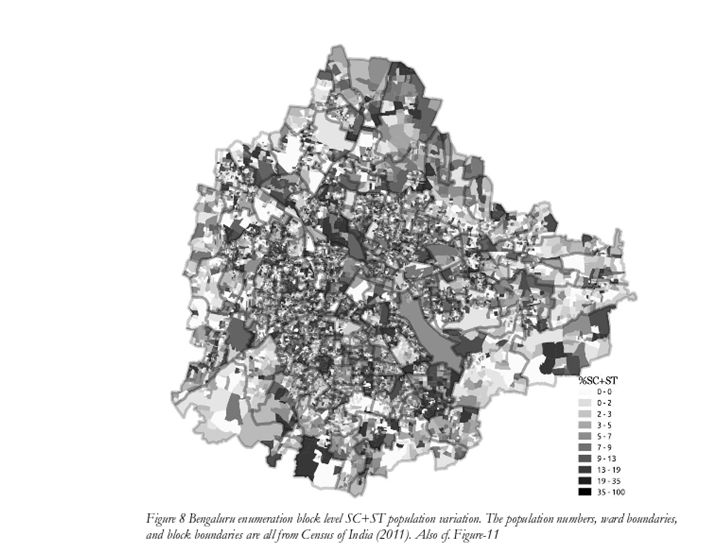

The paper authored by Naveen Bharathi, Deepak Malghan and Andaleeb Rahman brings out a detailed picture of the extent to which the metropolitan cities of India are segregated along the lines of caste, showing how the populations of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Dalits and Adivasis) are concentrated in particular localities or sub-localities.

The paper builds on a variety of work done on this subject in the past. The literature review suggests that the forces of modernisation, development and liberalisation have not done away with caste. Rather than becoming “melting pots” and places abound with possibilities for upward social mobility, the urban spaces mirror rural India’s social and economic realities. Even in cities which are “dominated by private sector - where individual agency, knowledge and competence create meritocratic hierarchies”, caste remains a reality.

An article by Vithayathil and Singh reveals, to a great extent, the segregation that exists in Indian cities. Their work gives percentage figures on how much of the SC/ST population in the particular cities would have to move to different areas to bring about an even caste distribution across the cities. It is 32.5 per cent for Ahmedabad, 36.4 per cent for Kolkata, 19.4 per cent for Hyderabad and 22.2 per cent for Mumbai. However, according to the new paper, these figures would themselves be an underestimate of the extent of segregation, as ‘wards’ have been used as the units of analysis; there can be intra-ward heterogeneity of the population.

Using census data, digitising and geo-registering it, the new study presents “the first visual portrait of the extent of caste based residential segregation in India” (for Bangalore city) up to the level of census enumeration blocks. Census enumeration blocks have around 100-125 households with population of 650-700 persons. The authors have built upon earlier works, such as the one by Trina Vithayathil and Gayatri Singh, by bringing the unit of analysis down to the level of census enumeration blocks as opposed to the level of wards. The paper shows how looking at segregation from the level of wards gives an inadequate picture of the realities of segregation as there is a greater level of intra-ward heterogeneity in population distribution.

The paper calls for future census data to be released at a geo-tagged enumeration block resolution as the paper had to use the analog version and digitising, if the Census of India can make the analog version public, there should be no reason not to make the digital version public. The paper also calls for a similar study on the lines of religious segregation and cites data limitations as the reason preventing the authors from carrying such a study out.

Many great intellectuals and social reformers, including Ambedkar and Jyotirao Phule before him, had advised Dalits to migrate to cities. Phule admired the liberty that the life in cities offered, and he was able to earn his living because of the economic freedom allowed in the city. Ambedkar advised Dalits to move to the cities to access the possibility of breaking free from caste-based occupations and the stigma of caste. He vehemently criticised Gandhi’s romanticism of the Indian village as glorification of a space that trapped Dalits. He famously said “The love of the intellectual Indian for the village community is of course infinite, if not pathetic. (..) What is a village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow mindedness and communalism.”

India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru also recognised the existence of caste as one of the major factors which was holding back India. However, Nehru was a strong believer in the power of modernity. The forces of modernity and economic growth would eventually overcome the traditional system. Such an idea is reflected to date in the thought of the middle classes.

While saying this, it is also true that the processes of modernisation, urbanisation and economic growth have to some extent waned the extent of oppression faced by Dalits. Additionally, migration has also enabled some freedom from occupations which were earlier imposed on Dalits. The point, however, is to remain critical of whitewashing the continued manifestations of the caste system.

What the paper also does is dispel the myth of a caste-free urban India. Caste segregation is not something that occurred in the past or only in villages. It is a fact in the glistening urban metropolises of modern India. Not only is the caste segregation occurring at the larger level of localities or even wards, but it is occurring at a micro level. Neighbourhoods and even streets are segregated on the basis of caste in cities. This calls for a radical rethink of urban policies and traditional ideas that urbanisation, economic liberalisation and capitalism will bring about the end of the caste system, need to be questioned.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.