Remembering BR Ambedkar as Agent of Change, Which Dalit Politics Urgently Needs

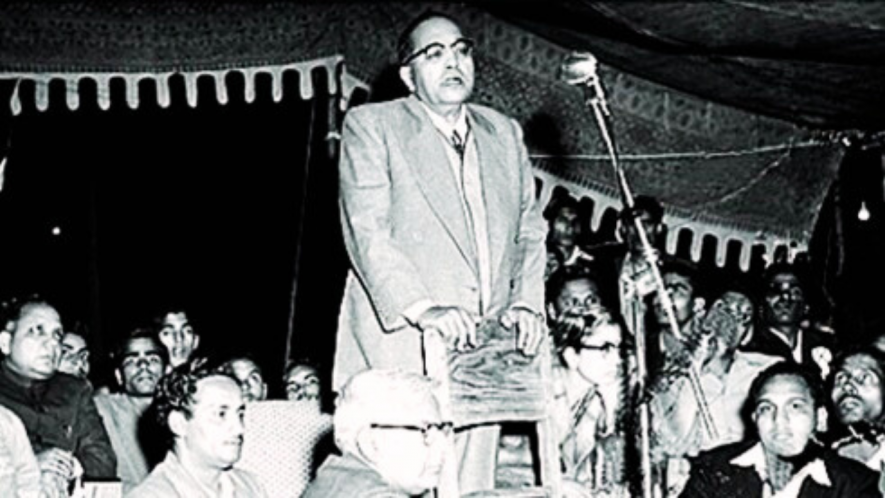

Dr BR Ambedkar at a public meeting in Delhi in 1955. | Image courtesy: getarchive.net

The sun of self-respect has burst into flame

Let it burn up these castes!

Smash, break, destroy

These walls of hatred.

Crush to smithereens this aeons-old school of blindness,

Rise, o people!

(Translated from a Marathi song on the 1970s anti-caste movement.)

On the birth anniversary of the first law minister, champion of Dalit rights and Constitution-writer BR Ambedkar, it is customary to recall his legacy at seminars, lectures, and exhibitions. But this year, while remembering his passionate voice for social justice, we should also acknowledge the sense of trepidation that has come to haunt these celebrations. An apprehension has arisen that the political and social fronts of the Dalit movement have deviated from the core values the nationalist icon espoused and the critical engagements that shaped his life. Now, sixty-two years after Ambedkar’s passing, we must acknowledge the tremendous changes in Dalit politics and society that led to the present-day conditions.

Ambedkar prescribed two paths through which Dalit communities could address their socioeconomic needs and demands—politics of agitation and representation in Parliament. Historically, through direct struggle, Dalit movements fought Untouchability and demanded an egalitarian society in which minimum wages, self-respect, dignity and land ownership were normatively assured. Fighting these battles made Dalit communities self-conscious about the need to transform India socially.

In 1950, Ambedkar, who headed the Drafting Committee of the Constitution, said in the Constituent Assembly that political democracy “cannot last long without social democracy”. Such a polity, he said, would have liberty, equality and fraternity as its core. Arguably, today, we need to remember these goals and that they remain as relevant as in Ambedkar’s time. The Dalit struggle for emancipation is far from over.

It is critical to examine the ideological degeneration and electoral decline of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), formed in 1985. (From just over 22% of the vote share in the 2017 Assembly election in Uttar Pradesh, it fell to getting, in the 2022 poll, to just below 13% of the popular vote.) But first, let us examine the role it played in politically empowering the Dalits.

In 1978, nearly two decades after Ambedkar’s death, Kanshi Ram and BR Khaparde set up the All India Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation or BAMCEF, a body to organise government employees from the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, backward castes and minority communities. BAMCEF was a think-tank of sorts for oppressed social groups. It tried to put Ambedkar’s words from one of his last speeches into action by encouraging the emancipated among the oppressed to “pay back to society”. It greatly influenced Maharashtra, especially in the Vidarbha and Marathwada regions. Kanshi Ram winning the support of BAMCEF and its members gave the BSP its initial base in Uttar Pradesh, paving the way for Mayawati’s assertion and rise to power.

Prakash Ambedkar of the Bharipa Bahujan Mahasangh (BBM) also rose to prominence in Maharashtra, but over the last decade, the influence of BSP and BBM among Dalit and backward communities—recognised as Other Backward Classes since the 1990s—has faded significantly. The decline in support from the communities they represent and the perception that they lack agency within the BSP and BBM were the primary reasons for this fall. And when such a situation arose, elite-caste leaders from political parties entered Dalit-Bahujan politics to play their surplus leadership role.

Through all these transitions, the Dalit intellectual class remained a mute spectator to the suffering of the Dalit masses and uncritical of the BSP’s leadership. As a result, it has been aiding the spread of success stories of elite leaders and parties representing elite-caste interests. They are not challenging the power of established elites even as the primary achievement of Dalit social and political movements so far—access to representation in Parliament—has failed to become widespread. While reservations were considered a safeguard against discrimination based on caste, religion and race and still shape reservation politics, the need for this representation to become decentralised is still unfulfilled.

It is also essential to look into the history of the demand for representation. The Rajah-Moonje pact signed in 1932 was the first agreement on reservations and a joint electorate for the depressed classes and the caste Hindus. It was something Ambedkar considered detrimental to the Depressed Classes, and six months later, the Poona Pact superseded this arrangement, and seats were reserved for the Depressed Classes. Of course, the demand for reservations is older. In 1922, MC Rajah, elected as a member of the Madras Legislative Council from the Justice Party, first demanded reserving seats in government institutions, including local bodies and municipalities, for members of Depressed Classes. While the demand for a separate electorate and reservation of seats in legislative councils and local bodies was brewing since the 1920s, leaders always differed over whether the Depressed Classes wanted representation or a separate electorate.

But today’s problem lies in the fact that the focus almost entirely rests on the reservation of seats, while the leadership of Dalits is emerging from just a few centres of power. Decentralisation of power and representation here would mean creating space for assertion for a wide section of Dalit and backward interests, individuals and communities. The Dalit movement needs to ask itself as it praises Ambedkar almost ritualistically—are its spaces for the struggle for justice turning into spaces of discrimination and exclusion? One point of analysis would be whether leaders from the lowest rungs of Dalit society can feel safe while having their voices heard.

Last year, the Dalit Sangharsha Samithi convener Narasimhamurthy ‘Kurumurthy’ was murdered in Karnataka, coming as a stark reminder that the burning issues of our time go beyond reservation, Untouchability and representation. The question now is not just to decry these crimes but ask who will fight the battle against institutional suicides/killings of Dalit students in premier educational institutes, who will prevent and assure justice for the brutal attacks against Dalit women, and the relentless frequency of deaths of septic tank workers.

The Union Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment reports an ever-oscillating scale of too many deaths in septic tanks since 2017. That year, 400 Dalits died while cleaning tanks, followed by 67 in 2018, 117 in 2019, 19 in 2020, 49 the year after, and 48 in 2022.

Today, even representation is being impeded by the monopolisation of Dalit voices by privileged figures. There is harassment, moral policing, and domination by higher castes or classes, while representation has become lineage or family-based, situated in urban spaces, and increasingly Delhi-centric. There is no attention to ensuring representation for the diverse social, economic, political, and regional backgrounds of India’s Dalits. Amidst all this, can we make the assertion every household of manual scavengers, drain-cleaners, and trash-pickers, is part of Ambedkar Jayanti celebrations?

On 18 March 1956, in his historic speech in Agra, Ambedkar expressed concern about the plight of rural landless labourers and charged the educated middle-class Dalit of being self-centred. He warned the gathering, saying, “Today, my position is like a pillar supporting huge tents. I am worried about when this pillar will not be in its place.” Dadasaheb Gaikwad, the founder of the Republican Party of India (RPI), took this warning to heart and began organising land movements, winning popularity after proving himself a strong Dalit leader. But the RPI twice suffered bifurcation and the dislike of the educated Dalit middle class.

In its fractured state, the Dalit movement could not focus on atrocities against Dalits and the rising unemployment and frustration among the masses. The Dalit Panthers arose as an off-shoot of the resentment and disenfranchisement of the poverty-stricken Dalit youth. Raja Dhale and Namdeo Dhasal became instrumental in organising people and posing questions to Dalit and non-Dalit leaders. But over time, ideological rifts arose within the movement. In 2001, Gail Omvedt wrote in “Ambedkar and After: The Dalit Movement in India” that the Dalit movement “failed to show the way to transformation because of late these movements are turning themselves into pressure groups”.

This brings us back to the reservation question. Reservation in government services was extended to the Scheduled Castes under colonial rule in 1942. Post-independence, the Constitution safeguarded this right of the Dalits, along with the rights of women, children and minorities. However, data released recently by the Union Ministry for Education reveals that 19,000 Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe and OBC students dropped out of premier institutes like the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) in the last five years.

The IIMs have seen 143 Scheduled Caste students leave, 133 from the OBC communities, and 90 from the Scheduled Tribes. From the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), 538 Scheduled Tribe students, 1,362 Scheduled Caste students and 2,544 from the OBCs have exited. In other central universities, 3,596 Scheduled Caste, 6,901 OBC and 3,949 Scheduled Tribe students left between 2018 and 2023. So we keep revisiting history but fail to acknowledge our historical mistakes every time, which still haunt a large section of society.

A tribute to Ambedkar will be meaningless if we ignore the fundamental questions of caste, egalitarian social order, and social democracy. Under the current regime, Bahujan autonomy, assertion and inclusion of the Dalit independent movement needs renewal, which means renewing the focus on varied issues. That would justify the dreams of Ambedkar to create a democratic republican society.

Bijayani Mishra is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology, and Anjali Yogi is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science, at Maitreyi College, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.