Caste is in the Very Air we Breathe

Representational Image.

Drawing from the US experience and action, India, too, needs to formulate policies to reduce the outsized exposure to air pollution of historically marginalised communities, writes Kalyani Tembhe.

—

A recent study published by Springer Nature examines how socio-economic conditions are a vital determinant on the level of exposure to air pollution of a particular social group.

Scientists from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Delhi and universities in the US and Korea analysed and quantified the inequality in the exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) based on the socio-economic status of communities.

Fine particulate matter, or PM2.5, are tiny particles in the air that are less than 2.5 microns in width. Emissions from burning of fossil fuels like coal, gasoline, diesel fuel, biomass or wood make up for most of the PM2.5 pollution found in air outdoors.

The smaller the particles, the more damage they cause to our health.

The analyses of the universities were conducted over 28,000 clusters, comprising villages in rural India and census blocks in urban India from the National Family and Health Survey (NFHS-4).

Findings

According to the study, an increase in the number of Scheduled Caste (SC) and Other Backward Class (OBC) households in a residential neighbourhood is significantly associated with an increase in the total PM2.5 exposure of that neighbourhood.

Further, neighbourhoods with a high prevalence of Muslim households have observed a significant increase in PM exposure over recent years.

An increase in the number of Scheduled Caste (SC) and Other Backward Class (OBC) households in a residential neighbourhood is significantly associated with an increase in the total PM2.5 exposure of that neighbourhood.

The study postulates that environmental injustice in air pollution exposure operates differently in urban and rural India.

This makes sense because the structural socio-economic disparities, which drive these environmental injustices, operate differently in rural and urban areas.

One of the interesting findings is how the results can differ according to the parameters used for such analyses. For example, the total PM2.5 exposure is low for clusters with prevalent Schedule Tribe (ST) households.

However, the evaluation of disparities in PM2.5 exposure from power generation, a key source of air pollution, relative to the benefits (electrification, nighttime luminosity) received showed that ST clusters face a significantly higher exposure as compared to the corresponding benefits.

This shows how environmental injustice is a multi-faceted problem and highlights the importance of defining the environmental justice parameters justly.

Examining the correlation

Although there is limited research examining the correlation between air pollution exposure and a community’s pre-defined socio-economic status in India, some studies have quantified these correlations.

A study conducted by scientists in the US discovered that air pollution from coal-fired power plants is more heavily concentrated in poor, marginalised-caste villages than in wealthier, dominant-caste villages.

Another study by IIT Delhi and World Resources Institute mapped the air pollution exposure disparity in rural parts of the country and found a strong correlation between the exposure distribution and socio-economic status.

A study conducted by scientists in the US discovered that air pollution from coal-fired power plants is more heavily concentrated in poor, marginalised-caste villages than in wealthier, dominant-caste villages.

These studies used data from the 2011 census of India which has limited socio-economic status information relevant to evaluating environmental justice concerns in India.

Hence, there is a need for more recent and exhaustive data to conduct accurate environmental justice studies that would inform environmental justice policy making in India.

While some studies around environmental justice have been conducted in the country, much more extensive work on environmental justice and air pollution has been done globally, and most of the environmental justice policy implementation has been carried out in the US.

The policy framework and experiences in the US can be used as a good reference for policy drafting and analyses in India.

Environmental justice policies in the US

Environmental justice activism, concerning environmental pollution such as that of air, water and landfills, has evolved over time.

Socio-political activism across the globe has tried to draw attention to how socio-economically disadvantaged and historically marginalised communities are unjustly exposed to environmental pollutants due to lack of political clout, structural disparities in the society or increasing hostility against them.

The onset of environmental justice activism can be traced to the US. The early environmental movement in the country, initially defined as “environmental racism”, concentrated on the unequal distribution of environmental liabilities on a social and spatial scale frequently overlooked by the mainstream environmental movement.

While recognising the socio-economically disadvantaged communities is important in addressing and acknowledging environmental injustice in any community, it is also equally important to recognise the structural issues that caused these disparities to ensure effective policy implementation.

An environmental justice policy or initiative can be rendered ineffective if these social mechanisms of disparity are not aptly defined and recognised.

In the US, Joe Biden’s administration implemented the Justice40 initiative to address the pollutant exposure disparity.

The initiative uses the ‘climate and economic justice screening tool’ (CEJST) to identify and prioritise disadvantaged communities for government programmes and funding based on climate and environmental burdens and socio-economic indicators.

The goal of this initiative is to ensure that at least 40 percent of the overall benefits of certain federal investments are received by the disadvantaged communities that are marginalised and overburdened by pollution.

However, a study by the Apte Research Group found that while the application of CEJST to guide ambient air pollution reduction measures may eliminate modest disparities in exposure by income and for disadvantaged communities, it may not reduce the larger exposure disparity by race-ethnicity.

Projections made by the groups showed that the emission reduction in disadvantaged communities will have more exposure benefits for the overall population than for the most exposed racial-ethnic groups and that the disparity in the air pollution exposure of marginalised Black, Hispanic and Asian communities will continue to persist, if not increase.

An environmental justice policy or initiative can be rendered ineffective if social mechanisms of disparity are not aptly defined and recognised.

Moreover, disadvantaged communities, as defined by the CEJST, entail roughly 34 percent of the total US population, and allocating 40 percent of certain federal funds to 34 percent of the population is more in line with equal distribution than equitable distribution.

The disadvantaged communities as identified by this initiative only have a slightly higher proportion of people of colour (especially Black, Hispanic and Indigenous populations) and low-income populations as compared to the national average.

The decision to exclude race-ethnicity as an explicit indicator in the CEJST obfuscates the racist underpinnings of the decades of policies and practices which helped create this racialised exposure disparity.

It also highlights the central hesitance to explicitly include race as a factor in federal policy or tool due to concerns about potential political and legal challenges.

Tackling this disparity in exposure will require a systematic assessment of how any proposed and existing regulatory policy and tool would impact the exposure disparity for different historically marginalised socio-ethnic groups, and in this case, race-ethnic groups.

The racist underpinnings of the US environmental regulations were recognised much before the CEJST initiative and there have been other measures to address different aspects of environmental injustice in the USA.

The Assembly Bill 617 of California was implemented to ensure community well-being and representation at the centre of air pollution regulation and the Executive Order (EO) 12898 was formulated to analyse the environmental impact a given federal activity would have on a historically disadvantaged community.

However, both these judicial interventions have fallen short of closing the relative disparity gap in air pollution exposure.

The EO 12898 is not legally binding and is a general guidance for federal bureaucratic actions to ensure non-discrimination in federal programmes and give underserved communities more access to information and opportunities to participate.

The AB 617 also has its fair share of challenges. Some of the key issues faced are limited resources, inadequate monitoring network, coordination amongst different agencies, and so on.

Policy drafting and implementation has to ensure the recognition of the disparate exposure faced by these communities and that they are given opportunities to participate in the decision-making process of environmental regulation.

Despite these shortcomings, the administration framework and the lessons drawn from all these EJ laws, initiatives and Orders provide us with a blueprint to emulate in India’s current air pollution legislation and policy.

A way forward

While in India air pollution is regulated through the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) initiatives, it is also important to factor in environmental justice in air pollution regulations.

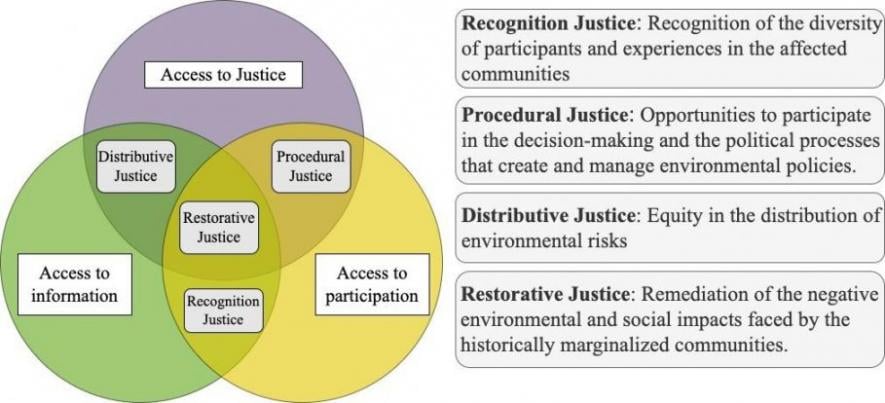

Any environmental justice policy intervention has three pillars: access to information, access to participation and access to justice. Within the ambit of these pillars, different aspects of environmental justice can be realised.

Figure 1:Types of environmental justice

Source: Compiled by Kalyani Tembhe

The gap of air pollution exposure disparity needs to be reduced and the negative socio-environmental impact faced by historically marginalised communities needs to be remediated.

Policy drafting and implementation has to ensure the recognition of the disparate exposure faced by these communities and that they are given opportunities to participate in the decision-making process of environmental regulation.

Thus, there must be an equitable distribution of environmental risks.

Drawing lessons from the environmental justice legislation in the US and the social justice studies conducted across the globe and in India, any environmental justice policy the Indian government formulates will be effective only if these basic principles are adhered to.

Kalyani Tembhe is an energy engineer working at the nexus of energy and environmental technology and policy.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.