Should Obama Withdraw the Stimulus Package NOW?

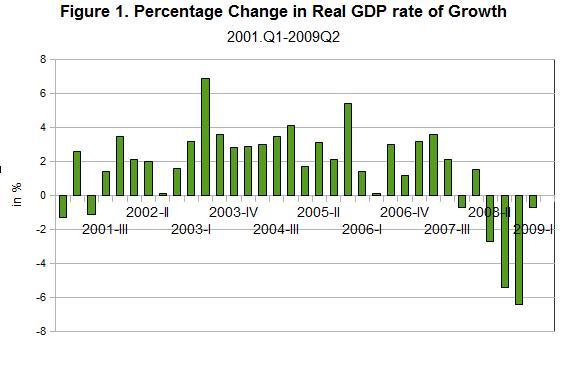

There has been much debate of late in the United States about the economy recovering from the worst crisis it has witnessed since the Great Depression of the 1930s. While the diehard conservatives are arguing that it is time to withdraw the stimulus package, there is some debate even within the Democrats, including some in the US administration on whether the government should `now' take a step back and let the market take over. There is fear among these sections of `overheating’ (fear of high inflation rates) in the economy if these steps continue for some more time to come. Fortunately though, the policymakers in the US administration have not yet started to believe it.

While it is true that the US is on a path of recovery, it would be an exaggeration to assume that they are out of the crisis. One obvious reason is that the US continues to witness a phase of deep crisis, both in magnitude and expanse, which cannot possibly be taken care of so easily and so little a time. The present crisis is not a normal textbook recession but it is a result of a very systemic flaw in the working of the US economy especially since the early 1990s. Enough has been written on the reasons and nature of the crisis so, that is not our primary concern here, though we would touch upon it just to put things in a perspective. Our focus here is to see whether the economy has indeed “almost recovered” as some have argued.

Let us first see what are the components of recovery, which could possibly throw some light on the extent of recovery. Since the US economy is facing a crisis of inadequate aggregate demand in the economy, the path of recovery has to somehow solve this problem. Its failure to do so would not only prolong the crisis but any premature withdrawal of the government stimulus would further aggravate the very problem it is seeking to address. Aggregate demand in any economy comprises of the consumption of the household sector, investment made by the household sector (residential investment), investment made by the corporations (non-residential investment), government expenditure and net exports (trade surplus).

As is known, the origin of this crisis lay in two crucial factors. First, the consumption as a proportion of GDP had been continuously increasing especially since the early 1990s. It was at its historic high in the first half of the present decade (close to 70% of the GDP compared to 61% in the late 1980s). This increasing share itself was a result of a substantial wealth effect generated through asset price inflation, both in the stock market and in the housing market. Asset price inflation of the kind that the US has witnessed since the late 1990s is unprecedented in its history. In fact, the stock market run of the 1920s paled in comparison to this. Therefore, even if the proportion of wealth against which consumption is made is low, if the magnitude of this wealth is phenomenal, it would generate a high enough wealth effect. An important factor to note here is that such a growth in the share of consumption, which increases the income multiplier1 in the economic jargon, is bound to be ephemeral in nature. Since the increasing asset market prices, both the stock and the housing markets, were the result of increasing speculation of wealth owners as well as financial corporations, any crisis in these markets would eliminate the wealth effect sooner than later, which is what seems to have happened (consumption share in GDP has either declined or stagnated in most of the quarters since 2007).

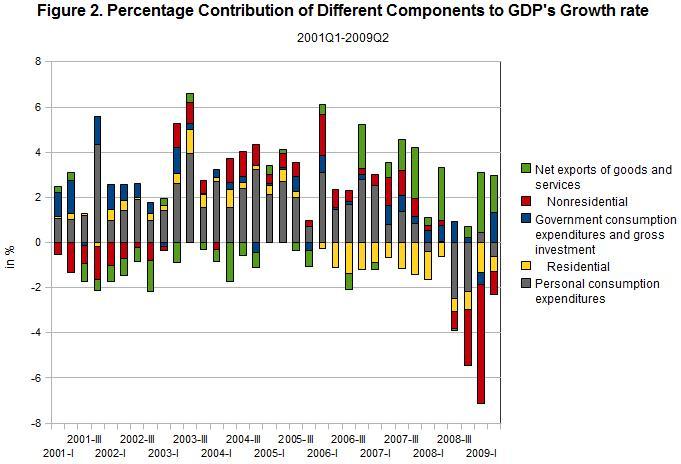

Second, the economic boom of the present decade, as is common knowledge, was driven by spectacular increase in residential investment owing to the speculative housing market (which The Economist had dubbed as the biggest bubble in the history of the US). What is interesting here that this was the time when there was a substantial slowdown in the non-residential investment. Therefore, one can safely argue that even though technically a large part of the high growth could be seen as `investment-driven', it was actually purely residential investment driven, so to speak. The importance of both these factors can be seen from Figure 2.

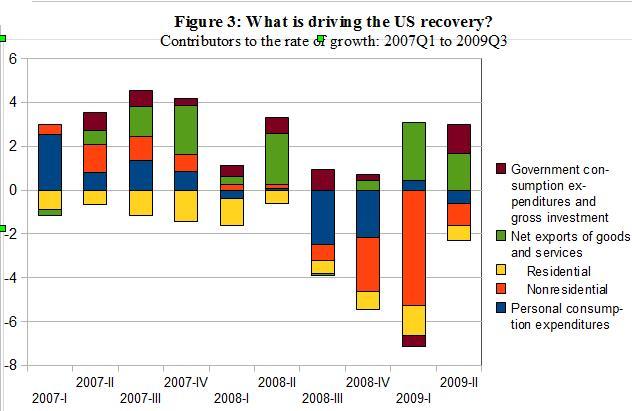

Herein lies the basic paradox that the US economy faces today. Not only has the residential market plummeted seriously, there has been a decline in the share of consumption too. Together they form a deadly combination of declining investment and the income multiplier. Therefore, the path to recovery has to be dependent on the last three components of aggregate demand i.e non-residential investment, government expenditure and trade surplus. Let us look at what is happening to these three factors at present.

Non-residential investment or the corporate investment in `real' capital continues to decline as a proportion of GDP, which itself is serious because it means a lower rate of growth in investment than the GDP. But this is a general trend during the periods of crisis. In any crisis, the first factor that is affected is corporate investment precisely because of the crisis of confidence of the capitalists. So, this by itself is not novel to this crisis, especially if we see it in the light of the magnitude of the present crisis.

The stimulus package that Obama administration has injected into the economy has led to increase in the second factor mentioned above i.e. government expenditure. This automatically has the effect of popping up demand and thus of GDP. But its magnitude is crucial, especially in crises like these. First, it has to compensate for the decline both in residential and non-residential investment. Second, even if that is taken care of, the net effect of that increase would be dampened if the income multiplier is decreasing as a result of declining share of consumption (as explained above). Therefore, the increase in government expenditure has to take care of both these factors which demands for more than what President Obama has announced so far.

Finally, the third factor i.e. the trade balance can also play a role in the recovery. In fact, as we will see below, the most crucial factor contributing to whatever little recovery that the US is witnessing today is directly linked to what is happening in their current account. Though it might seem contrary to common perception that current account balance in the US, which has been running record deficits for the last two decades, could actually be a catalyst to recovery. But if one looks carefully, if the rate of increase of trade deficit is low compared to the rate of decline in growth of GDP, it could actually play a positive role in recovery. In other words, if the `leakage' of income from the economy in the form of net imports declines during the crisis, it will put less downward pressure on the rate of growth. This is what seems to be happening in the US. The share of trade deficit in the GDP has declined during the period of the crisis giving a positive impetus to an otherwise declining rate of growth.

A decline in the trade deficits could happen if there is an increase in the share of exports in the GDP or a decline in the share of imports or both. Or, at least the decrease in the share of exports in the GDP is lower than that of imports if both are decreasing. Declining trade deficit has taken place during this period in the US due to a sharper rate of decline in imports than exports. Further categorization of imports reveals that two factors, namely, industrial supplies and materials( except petroleum and products) and automotive vehicles, engines, and parts together have accounted for more than half the decline in imports in these quarters. This nature of decline in the share of imports in the GDP seems more to be of a short term character than a policy response by the US to increasing trade deficits, which makes this component of recovery even for a medium term suspect.

After analysing various components of demand and their behaviour during the 'recovery period', we can say that the increased government expenditure in the US through the fiscal package has still not been able to stimulate the economy to the extent of alleviating the problem at hand. On the one hand, consumption has stagnated, thereby, terminating the route to recovery through an increase in the multiplier. On the other hand, neither the residential investment nor the non-residential investment is showing any sign of recovery, especially since the level of confidence of the corporations to invest is still quite bleak. Therefore, it would be prudent for the Obama administration not to withdraw the stimulus just as yet. Otherwise they would face what the US had faced during the Great Depression viz. the decision to withdraw the stimulus based on the initial signs of recovery ended up in prolonging the crisis which eventually lasted for almost a decade.

Notes

1 Income multiplier measures the increase in GDP with a unit increase in non-consumption components of the GDP. A unit increase in any of these components at first generates an equal amount of GDP. This increase in GDP, however, generates extra consumption since consumption is proportionate to GDP. Thus, the final increase in output is more than the initial one unit increase, which is where the name `multiplier' comes from. One could notice that the higher is the proportion of consumption, the higher would be the net increase in output.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.