Surat Court Throws Rule-Book, Baby, Bathwater and Tub of Criminal Defamation at Rahul Gandhi

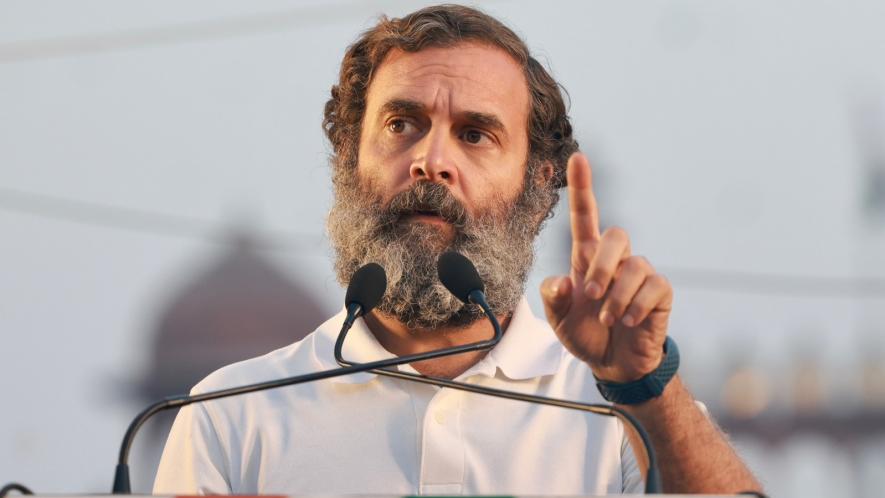

Image courtesy: bharatjodoyatra.in

The law of criminal defamation came into the Indian Penal Code from its very inception in Macaulayan times. The basic logic of making defamation a criminal offence was to prevent people from fighting in the streets to protect their honour or that of their loved ones. The law dates back to a time when duels were not unknown and came with their attendant fatalities.

When the Constitution of India was brought in, the right to freedom of speech and expression was made subject to the laws of defamation and contempt of court, along with a few other exceptions. Free India ought to have done away with defamation as a crime and continued with defamation as a civil law, which envisages compensation in terms of damages. The payment of damages in civil defamation cases is not unknown in the world. In fact, heavy damages are often a way to maintain the societal balance. For example, right now in the United States, Dominion Voting Systems is pursuing a civil defamation case against the Fox Network and other Trumpist media for disparaging its voting machines. There is no question of imprisoning somebody in the United States today for defamation. In fact, India is one of the rare countries where the criminal law of defamation still continues.

The constitutionality of criminal defamation was challenged in the Indian Supreme Court, but in 2015, in the Subramanian Swamy case, the court upheld sections 499 and 500 of the penal code, arguing that the provision had existed in the statute books for a long time. It was also argued that the makers of the Indian Constitution had themselves made an exception in the freedom of speech provisions in favour of defamation laws.

Let us come to the case of Congress leader Rahul Gandhi. Yes, it is a political case, but the process has been legal. There are two statutory provisions in play here. One is in the Indian Penal Code, which determines a maximum two-year sentence in such cases. And there is the Representation of the People Act, according to which anybody convicted with a sentence of more than two years invites disqualification from Parliament or the State legislatures.

In 2013, the Supreme Court held in the Lily Thomas case that a disqualification under the Representation of the People Act starts immediately after the pronouncement of a conviction and does not await the outcome of an appeal. To overcome this, the Manmohan Singh government came up with an ordinance whose effect would have been to provide some time to a convicted person. It would have saved convicted persons from disqualification until their appeal was sorted out. That ordinance could not become law because Rahul Gandhi, before a gathering at the Press Club of India in Delhi, tore up the text of the ordinance.

Today the legal position—which is not entirely of Rahul Gandhi’s making—is that a magistrate in Surat, Gujarat, has decided to throw the rule-book, the baby, the bathwater, and the tub of criminal defamation at him. He has been given an unprecedented maximum sentence of two years under the defamation law, and so the guillotine of disqualification has also fallen on him. It is an open question whether the magistrate had thought through the impact of pronouncing the maximum sentence. The magistrate’s court in Surat has allowed Rahul Gandhi to appeal its verdict and suspended the sentence for 30 days until that appeal is filed.

But in the appeal process, Rahul Gandhi needs more than a stay on the sentence. He needs the appellate court to stay the conviction itself. If, instead, he secures a stay of the conviction, Parliament may take that stay into account and keep his disqualification under suspension also.

There are no specific precedents in this regard. But the privileges of Parliament are wide and capable of being creatively used in a statesman-like manner. Recently, in the Uttar Pradesh Assembly, the case of Samajwadi Party leader Abdullah Azam Khan came up in the context of disqualification. Abdullah, the son of Azam Khan, was disqualified for ostensibly having provided false documents concerning his age. In an appeal against that sentence, he had failed to get the conviction stayed. And as a consequence, a by-election in his constituency, Rampur, was immediately announced.

Much also depends on what the Election Commission of India now decides to do. If it were to call for a by-poll in Wayanad, Rahul Gandhi’s Lok Sabha constituency, it would be anomalous if, at a later stage, the conviction against him is stayed or averted. If such a situation arises, a disqualified member would be within his rights to stake his claim to the seat. Therefore, it is incumbent on the Election Commission not to take a hasty decision without considering its wide-ranging and longer-term effects.

The author is a Senior Advocate at the Supreme Court of India. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.